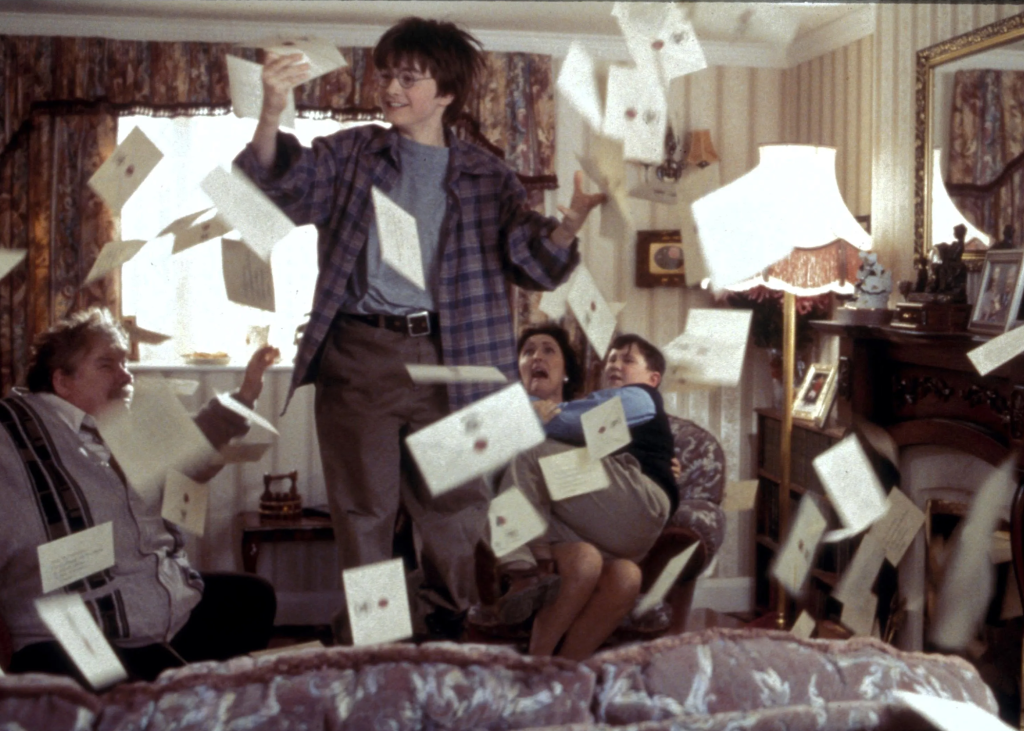

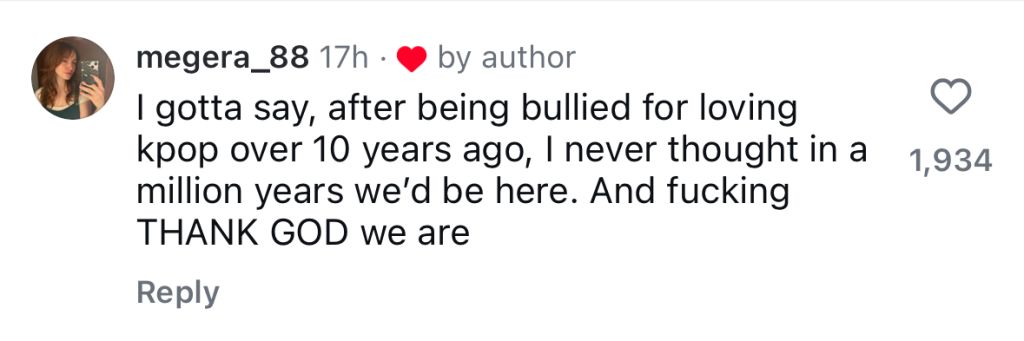

While Korean pop music, or K-Pop, has long been a global force, in previous years it has felt stigmatised and misunderstood in mainstream Western culture, mostly reserved inside its own niche. While hits like “Gangnam Style” or “Dynamite” by groups like BTS captured widespread attention, much of K-Pop’s deeper cultural influence remained confined to passionate fandoms. “K-Pop Demon Hunters” has flipped the narrative on its head. Since its release on Netflix six weeks ago, K-Pop is no longer something fans have to explain or defend – it’s now the centre of attention.

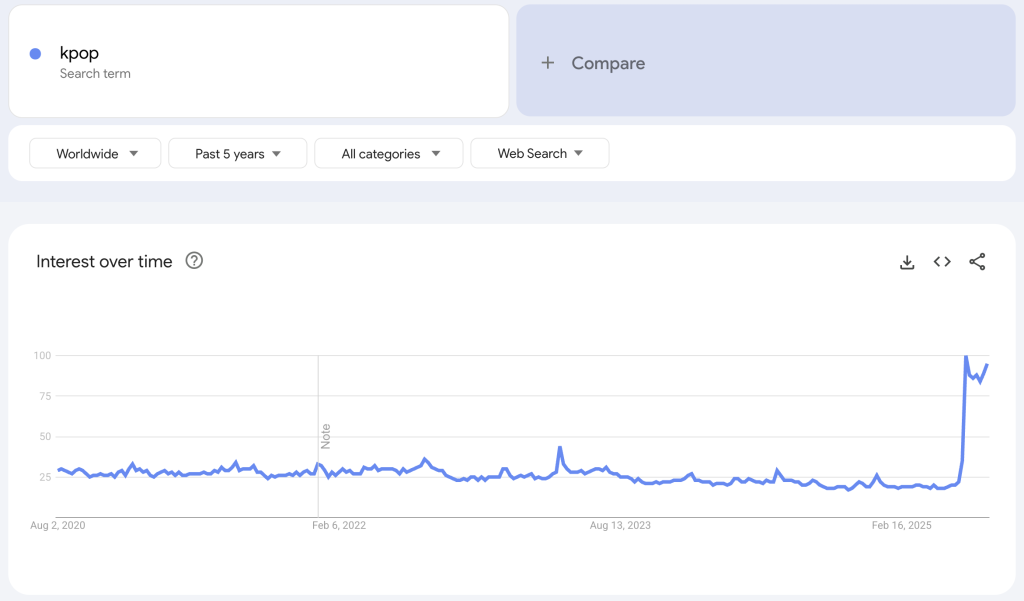

Since the film’s release on June 20th, social media has been flooded with memes, edits and discourse regarding the film – and the Korean music genre has blown up as a result. The soundtrack currently takes up seven out of the top fifteen ARIA chart positions, with the song “Golden” dethroning Justin Bieber for the top spot five weeks in. It’s even in talks to win the Oscar for Best Original Song at next year’s ceremony. Look, I’m not complaining.

Wait, sorry, let me just make that clearer. That’s the film’s ENTIRE SOUNDTRACK on the charts, by the way.

The fictional girl group HUNTR/X isn’t even the only one with newfound success. Katseye, a real group, made up of real people, has also shot up in popularity. They’re not even technically a K-Pop band (although they take heavy inspiration and are managed by HYBE, a massive Korean label) and yet the “KDH” hype is affecting them too. Suddenly K-Pop isn’t just popular, it’s cool.

KDH and the Democratisation of Pop Culture

Since the meteoric rise of TikTok during the pandemic, popular culture has not only been democratised, it’s become increasingly more fickle. Overnight, the established formula of record labels, media outlets and TV deciding what was popular disappeared, leaving us with pop stars such as Addison Rae, Dua Lipa, Doja Cat and PinkPantheress. When they became big, these artists had no formal label, no marketing budget and no team. They were just a single person who happened to upload a video onto the TikTok platform, which happened to resonate with the (insane) 1.8 BILLION active users worldwide. Yes, that’s almost a quarter of the entire world.

Of course, Netflix does happen to have a rather large and powerful marketing team, but it wasn’t marketed in the traditional sense. I don’t know whether the streamer ever believed in it or foresaw the success “K-Pop Demon Hunters” would have.

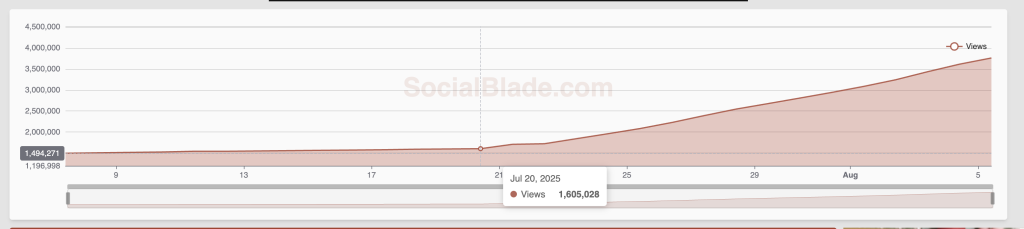

I think I maybe saw ONE trailer for the movie back in May, but it was barely advertised in traditional media. It wasn’t even mentioned as ‘upcoming’ on the Netflix homepage, and released quietly with very little fanfare. However, about a week in, it was picked up by the all-mighty social media algorithms and skyrocketed. In fact, the social media analytics site SocialBlade shows that the trailer didn’t even take off in popularity until after the film was out already, with a steep incline in views after June 20th.

While the streamer has since jumped on the bandwagon with memes, behind-the-scenes footage and more, I believe the growth of the movie was almost entirely organic (with a rather large asterisk here). Hell, even I told every single one of my friends to watch it (I’m still working a few of them, you know who you are). And as social media always is, if you like one post about a Demon Hunter, suddenly your entire feed is a sounding board of how great the movie is. And edits of the movie. And live-action performances of the songs – we’ll get to this later.

Aaand here’s the asterisk: this isn’t to say that the growth wasn’t nudged along by some clever invisible marketing. Social media is no longer a lawless Wild West, but a carefully studied algorithmic poker game. Netflix was playing the numbers game with “KDH”, even if it didn’t lead with a traditional media marketing push. While yes, the film became popular because of word of mouth and the fans, there is absolutely some manipulation at play.

However, this strategy leads to the success of the movie feeling more rewarding. It doesn’t feel like it’s being shoved down your throat by a big corporate entity, it’s being shoved down your throat by your friends. Due to the peer-to-peer way it grew in popularity, it’s built a genuine community of fans who care about it deeply, something incredibly rare in the modern film industry. I mean, just look at the latest releases from Pixar – they were marketed much, much more aggressively and yet don’t seem to have close to the lasting impact “KDH” has had on popular culture.

Due to Netflix being cagey about budgets and earnings, this is hard to quantify in numbers, but just think about it; have you ever heard anyone talk about “Elemental”? What about “Turning Red”? Didn’t think so. What makes “K-Pop Demon Hunters” so unique is how it was claimed by the internet, not presented to it.

The (Manufactured) Art of Pop Music

Even though marketing has changed drastically in the last few years, there is of course still one variable the studios can control: the content itself. When release day rolled around, “K-Pop Demon Hunters” already had a leg up in the virality department due to it being, in essence, a musical. Instead of having only the visual chance to hook people, the nature of the story meant the studio could lean into decade-old tricks used in the pop music industry to make it catch. And catch it did.

Instead of a normal K-Pop group’s format, who would develop songs written around their fandom, the studio was able to generate the fandom around their songs. The music in the film isn’t tacked on, or even explained away by an animated stage performance – it’s literally woven into the fight scenes and character moments between the girl group HUNTR/X and their rivals, the Saja Boys. The bands even have their own fandoms within the movie, with fictional ships and fictional TikTok dances setting up real ships and real dances within the real “KDH” fandom.

The album is even produced to be an earworm. Everyone who has seen the film (myself included) has said they’re completely unable to get the soundtrack to leave their heads, and it’s not a coincidence. To accomplish this, Sony Pictures brought on the music production team at THEBLACKLABEL, who had previously worked with legendary K-Pop artists such as BLACKPINK, ROSÉ and more. The producers even used a wide variety of tricks to get these songs to stick, which I’ll leave the explaining of up to the following music theory expert:

@brettboles Long overdue video! Drop a “waitlist” in the comments to be added to our upcoming rollout of the most accessible songwriting education platform EVER. #themtea #songwriting #kpopdemonhunters #whatitsoundslike #musictheory

What I can talk about however, is the incredibly clever way that the film explains away all of these criticisms, and manages to turn them into… commentary? It’s actually kind of genius; of course the songs are manufactured to be catchy, they’re being performed by demons to steal your soul. Of course there’s an in-universe fandom, they’re a K-Pop group, what do you expect? The nature of the film’s story completely flips this intentional groundwork for virality from something to be villainised into something almost satirical, and embraces its pop music roots rather than disguising them.

It’s almost devilishly clever, and makes the film come across genuine, instead of performative. And when the time came for real-life fans to find something to attach onto, the fandom was already there. The songs were already being played on in-movie radios, and the fictional dances converted to TikTok seamlessly. This all grew the potential of the film to find an audience, before it ever even came out.

Transcending the Medium of Animation

Finally, we need to talk about the impact that “K-Pop Demon Hunters” has had not just within the confines of an animated movie, but on wider fan culture around the world.

Even in far-removed Sydney (where I live), everyone is talking about it. Somehow, even Oxford Art Factory is running a KDH–themed rave, the University of Technology is running a screening as a movie night, and around the world, real K-Pop bands are performing the songs at their shows. Again, I want to stress the irony that these bands are portrayed as demons in the film, and yet the songs by the Saja Boys are being sung front of thousands. It is pretty cool though. Also, you better believe I got tickets to that club night.

The last time I can remember a film having this much of an impact outside of its own medium is “Frozen” all the way back in 2014. Of course, at the time, “Let it Go” jumped to the top of the charts (I even have vivid memories of hearing it in a doctor’s office), and funnily enough it won the Oscar for Best Original Song the year after. Sound familiar?

All of this helps to solidify “KDH” as a cultural zeitgeist this year. It has well and truly transcended not just the animation medium, but its status as a film as a whole. It’s become a community, maybe the first fandom in a long time that has moved outside of the genre it started in and into the mainstream eye. And honestly, it’s kind of refreshing to see.

In an age when interests on the internet are so varied, and people generally stay within the confines of their niche algorithms, it’s nice for everyone to agree on something for once. Even if it was engineered specifically to appeal to the masses by a giant streaming corporation – and it definitely was – who cares? Ultimately, the shift in popular culture in recent years means that it became big because of the collective viewers, and because this film connects with people. For better or for worse, we control the narrative now.

The film also exemplifies the rise of participatory culture within fans. It’s no longer the age of content consumption, but a new one of interacting with it. The amount of remixes, edits and commentary I’ve seen online highlights how the fandom has taken something that would usually be stonewalled behind a legal barrier (thanks Disney!) and made it their own. The line between the content and the audience has blurred, with each feeding and growing off the other.

And look, maybe the real winner in this situation is Netflix. After all, they’re the one reaping in the rewards of a brand-new hit franchise. But if it means we’re getting more original art (and make no mistake, “K-Pop Demon Hunters” IS art) and more creative stories from inspired filmmakers, I’m not complaining. Yes, it might be made by a giant studio to be as algorithm-friendly as possible, but it took of a life of its own the second it was adopted by the community. That, to me, is still worth celebrating.